Turkey as the Kremlin Pitstop

Understanding the impact of loopholes in sanctions on Russia

When my wife and I lived in Boston, we owned a condo that was a little quirky in its layout. There were a lot of nooks and strange angles to the roofline. It had plenty of windows and great light, though as any New Englander knows, great light also means a lot of drafts. So we obsessed over insulating the house as best we could. This proved futile in our early years, when during one sub-zero day, while we were visiting with friends and freezing in Vermont instead of at home, (seemed like a good idea at the time), our pipes froze. We returned to a disaster. The culprits? Squirrels. They had nested in the eaves, tearing out a small amount of insulation. That little gap rendered all our hard work in the insulation everywhere else somewhat useless.

I have been reminded of that lesson while in New Europe this year as I learn more and more about the efforts to sanction Russia in response to the Kremlin’s war on Ukraine. I have tried to track the coverage and political discussion in the US around the effectiveness of the sanctions, and often the framing reveals some blind spots. Colleagues at CSD have been tracking Russian exports of gas, oil, and oil products. Their work reveals some gaping loopholes.

Let’s start with the basics. Russia’s economy depends on oil and gas exports. The EU sanctions explicitly bans the importation of coal, other solid fossil fuels, crude oil, and refined petroleum products, “with limited exceptions.” One example of a “limited exception” was a derogation granted to Bulgaria that allowed Lukoil to continue to import oil to refineries in Burgas on Bulgaria’s Black Sea coast. CSD’s energy team collaborated with The Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) and Global Witness to track the flow of this oil, revealing that this loophole garnered the Kremlin over $2 billion in revenue.

While the EU sanctions allowed temporary exceptions to “EU member states that, due to their geographical situation, suffer from a specific dependence on Russian supplies and have no viable alternative options,” CSD and partners found that oil sent to Burgas then found its way outside of Bulgaria. From a report last December:

“In most cases, the low-quality fuels are transferred to ships carrying higher-quality products, increasing the value of the final exports, and thus, the profit Lukoil is generating. CSD analysis reveals that the fuel products have been sold to a range of countries including the U.S., Egypt, Turkey, and Nigeria, among others. CREA’s analysis of Kpler data reveals that between April and October 2023, three shipments carrying more than 600,000 barrels of fuel products from Lukoil worth around $62 million engaged in an STS transfer (mostly near Greece) with a final destination at different U.S. ports in Florida, New York and Houston.”

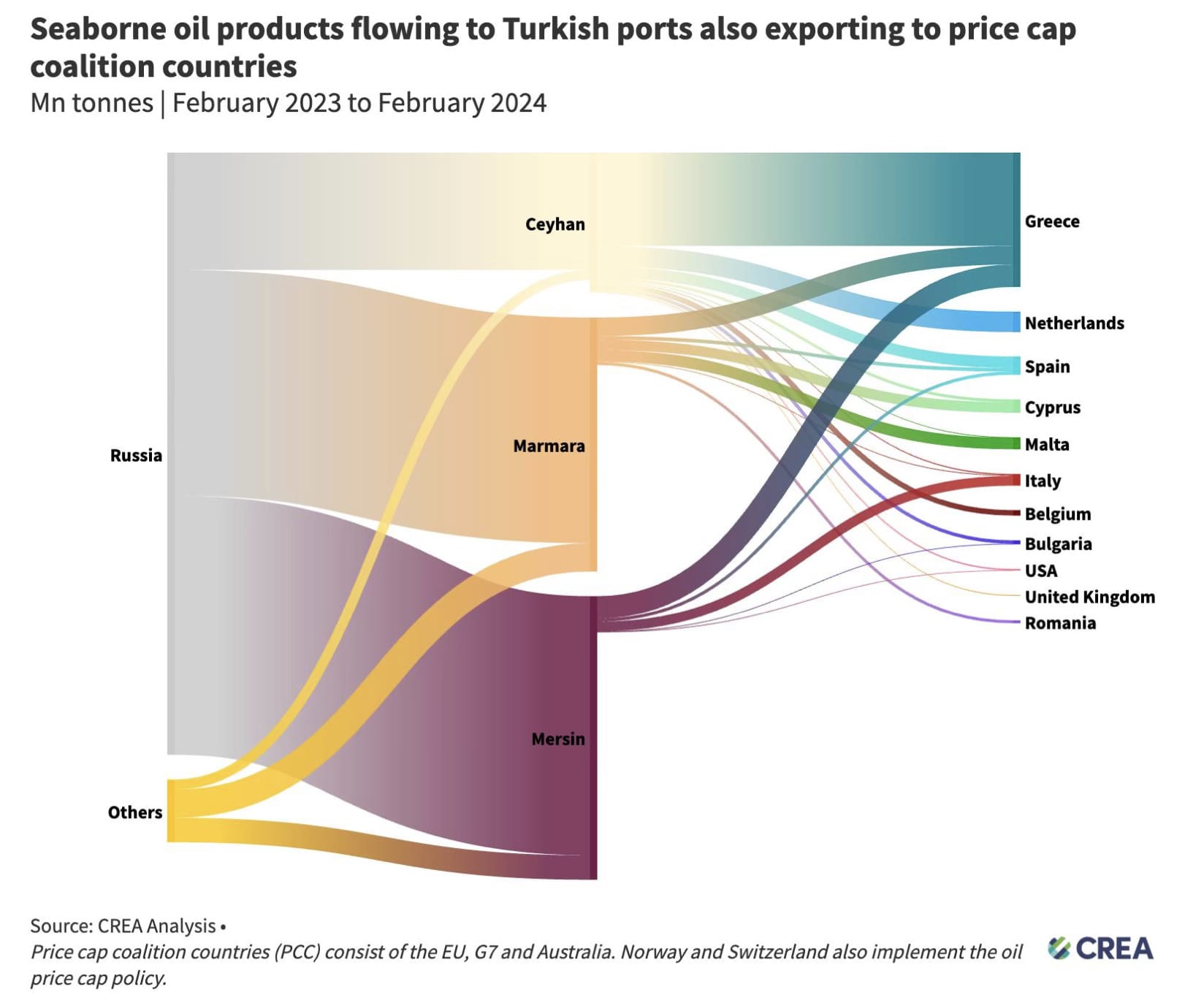

This month, CSD and CREA released a new report on the role of Turkey in facilitating the sale of Russian oil and oil products. Turkey, while an important member of NATO, refused to support the sanctions on Russia. This role has enabled it to become a major hub for Russian goods. Turkey became the biggest purchaser of Russian oil and oil products in the world in 2023. It seems that those goods are not simply going to other non-participant nations.

In their recently released report, Kremlin Pitstop: Financing Putin’s War, CREA and CSD estimate that between February 2023 and February 2024, the EU imported 3 billion EURO worth of oil product from Turkish ports. Given how much Russian oil these ports receive, that 3 bn is buying a lot of Russian fossil fuel products. As the report points out, these oil products are coming from Turkish ports that do not have refineries, and 86% of the oil products in these ports comes from Russia.

Thank you for reading Notes from New Europe. This post is public so feel free to share it.

A few other key takeaways from CREA and CSD’s comprehensive analysis:

● Since the start of the EU/G7 ban on 5 February 2023 until the end of February 2024, Turkey has imported EUR 17.6 bn of Russian oil products, a 105% increase compared to the same period the prior year. Since the introduction of the ban, 81% of Turkey’s imports of oil products have been from Russia, showing an increased reliance that could threaten their energy security.

● Turkey’s domestic consumption of oil products grew by 8% in 2023. In contrast, the country’s seaborne imports of oil products grew by 56% suggesting that Turkey is becoming a re-export hub for oil products, not just satisfying a growth in domestic demand.

● Russia’s exports of oil products to Turkey generated EUR 5.4 billion in tax revenues for the Kremlin war chest, prolonging and enabling Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

I encourage you to read the full report from CREA and CSD here. For the journalists among you, or heck, for all of you, I suggest you to dive into the details (including some policy recommendations), and then step back to take in the bigger picture. In our efforts to consider the full scope of Russia’s war on Ukraine, the topic of sanctions evasion needs more attention. The way we frame this conflict is critical. We need to help people understand how the Kremlin is waging this war beyond the direct violent warfare strategy. By doing so, those of us far to the west of Ukraine can better understand our own involvement. And in this year of elections, perhaps we can also better understand the stakes of the decisions our elected officials make–more as members of government, elected to govern, than as politicians.