Losing ground on the information front

Declining press freedom in Slovakia

Six years ago I went to Budapest to speak with people there about the impact of Victor Orban’s highly effective strategy of weakening independent media through domestic media capture. One of my meetings was with Michael Ignatieff, the president of Central European University, a model of higher learning for the region and Europe. The situation for people and organizations that did not get on board with the Fidesz Party’s consolidation of power was such that soon after that visit Ignatieff announced that CEU would effectively move to Vienna, to protect academic freedom (and to protect academics).

It was a bleak, gray picture (in a glorious, beautiful city), with only thin rays of light. In search of something more hopeful in the region, I took a brief detour to Bratislava, Slovakia. I had heard of a burgeoning podcast ecosystem in Slovakia, and I wanted to talk to Dávid Tvrdoň. Dávid was central in jump-starting something of a podcasting ecosystem as part of an overall growing independent media community in Slovakia, well ahead of other countries in the region.

Thanks for reading Notes from New Europe! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

I had always been fascinated by Slovakia. The country that gave us 1968 legend Alexander Dubček, the wonderful Marek Hamsik, and a long history of crafting some amazing wooden toys. As with most American journalists, it rarely—if ever—came up in my editorial meetings, save for when we needed to correct ourselves and say “I’m sorry, not Czechoslovakia…I meant Czech Republic.” (Slovaks just LOVE that mistake. And they want you to know that they are not at all like Slovenians). In 2018, Slovakia represented possibility for journalism and independent media.

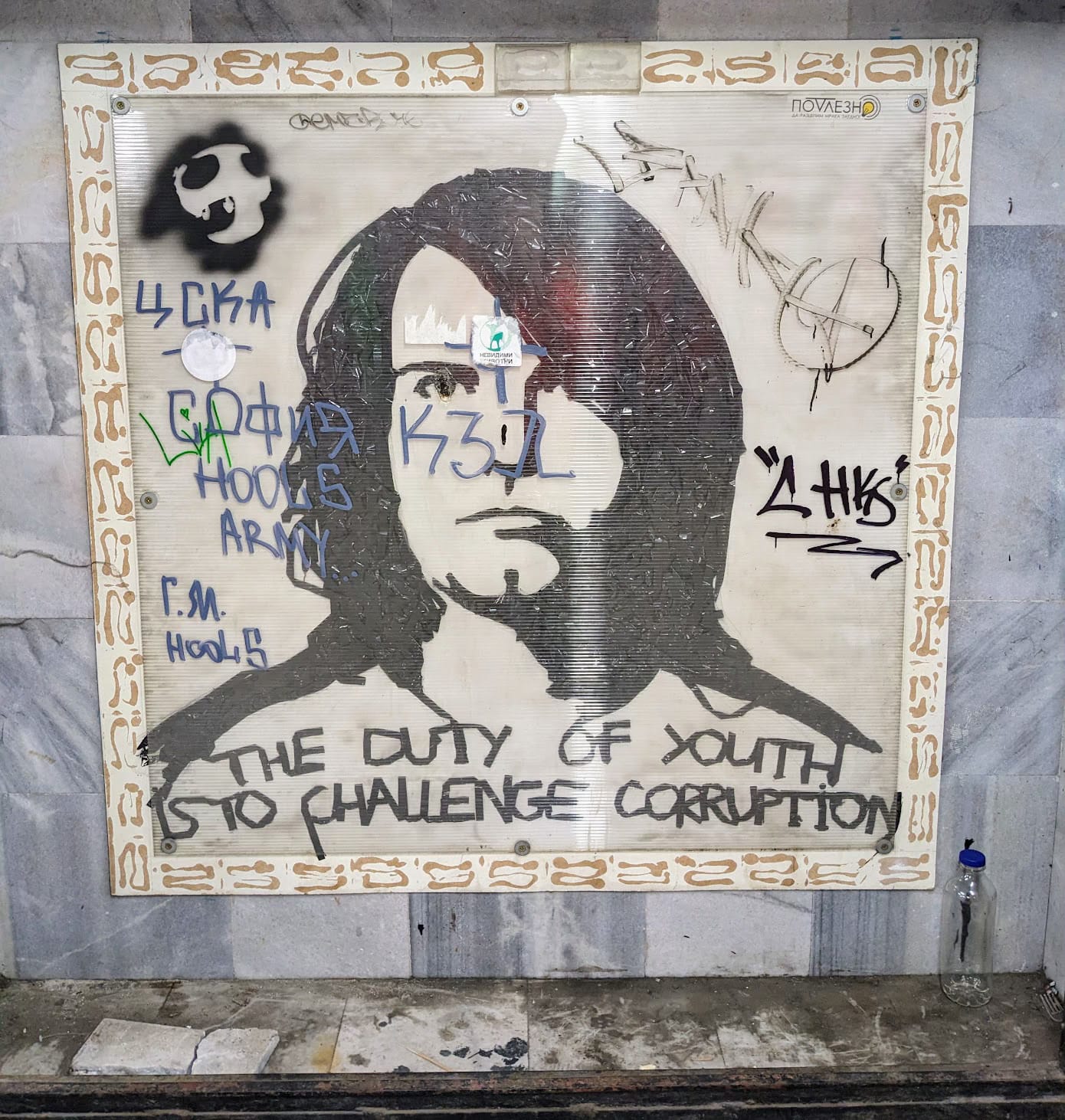

Earlier that year, Slovak journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancee Martina Kušnírová were murdered. Kuciak had drawn attention for robust reporting on fraud within Prime Minister Robert Fico’s circle of influence. A sickening tragedy, much of the nation took to the streets to call for an end to corruption and the increasingly authoritarian ruling party, Smer. Dávid and journalists at fiercely independent media like Dennik N and SME, like Kuciak, had been committing strong acts of journalism for some time. The collective response from the public encouraged them to push even harder.

Not coincidentally, when Russia attacked Ukraine in 2022, Slovakia was quick to send arms to support its neighbor. This despite Slovakia being, along with Bulgaria, one of the country’s in the region with the strongest pro-Russian sympathies. It is hard to imagine such strong support had Smer remained in power. And now, they are back.

This fall, Fico came back into power and a new reality is stepping in. Or a new old reality. In October, Fico announced that Slovakia would no longer supply arms to Ukraine. And roughly six years from the day Ján Kuciak and Martina Kušnírová (say their names) were murdered, Slovak journalists are sounding the alarm. And scholars tracking the Kremlin hybrid warfare tactics see this as a highly predictable result of Kremlin gaining ground in state and cognitive capture from election results last fall. And Hungary serves as an example of the effectiveness of authoritarian leaders stifling pesky and inconvenient acts of journalism, and the fear is that Fico is following the Orban playbook.

Writing in The Fix last week Dávid noted, “since the new Slovak government led by Robert Fico in his fourth term as prime minister was formed, pressure on independent media in the country has increased.”

I prefer more positive excuses to reach out to Dávid, yet it feels necessary to have him help us better understand what is happening.

GG: Dávid, thank you for offering some time. IIn your piece in The Fix, you write, "Jan Kuciak and his fiancée. It’s been six years since they were murdered in cold blood in their own home. I remember at the time we as journalists and society as whole felt like the country hit rock bottom."

Remind us what happened after that murder. From afar, it seemed that people across the country rose up against the rising authoritarianism....

Dávid: After the murder, Smer, the ruling party was pushed to make changes in response to the massive demonstrations and pressure from the Most-Hid political party. While Most-Hid was the smallest party in the ruling coalition without them the coalition lost its majority. So Fico decided to step down together with the Minister of Interior. Fico’s prodigy Peter Pellegrini, who is now running for President in the upcoming elections in Slovakia, was chosen to form a new cabinet after Fico’s resignation. Later, the police chief was replaced.

Pellegrini’s government finished the election cycle just before the Covid-19 pandemic hit. After the general elections in 2020 every political pundit thought Fico was finished and there is no return. His party was polling at its historic lowest numbers and the levels of trust in the public showed him personally polling last among all the political leaders.

A few months into the pandemic and all the missteps of the wide coalition of four parties from both the conservative and liberal side led by Prime Minister Igor Matovic, Fico and his fellow party members fairly quickly jumped on the antivax narrative. That turned out to be just enough fuel to give Fico and his Smer the velocity they needed. Later they started pushing more and more agenda you could have heard by the government in Hungary or Russia.

GG: Now fast forward to the elections last fall, when Fico returned from political exile. What were some of the reasons people were ready to overlook the past atrocities (esp toward journalists) and vote his party back into power?

Dávid: As my colleague from daily SME, deputy editor Jakub Filo, put it after the election results in October 2023: “On the wave of conspiracies, lies and unbridled anti-democratic populism, Robert Fico was able to appeal to more than 23 percent of voters and will have 40 deputies in the parliament.”

As another colleague from daily SME, op-ed writer Peter Tkacenko, likes to remind everyone, Fico is the most talented politician this country has seen in decades. And as another journalist, deputy editor Konstantin Cikovsky of Dennik N, once said, it’s hard to imagine what this country might have looked like if Fico used his skills to serve the public and not himself and his immediate circle of lackeys.

Third, let’s not forget how many countries were in chaos in terms of public trust after the pandemic. Unfortunately, Slovakia stood out even in the pandemic. When most opposition politicians tried to help the discourse and not heighten the tension, Fico and his fellow party members continued to push anti-vax narratives. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Fico and co. doubled down on pro-Russian sentiment and pushed anti-war messages from Russia aimed against NATO and EU for arming Ukraine and prolonging the war.

GG: Tell us about what you are witnessing with journalists effectively under attack and either stepping back from journalism or tempering their criticism of the government. How dire is this retreat, and what does it say about the progress of media capture in Slovakia?

Dávid: In some regards, independent Slovak news media has been a success story. When donors from the West looked at the CEE region in the past few years, they mostly didn’t identify Slovakia as vulnerable to media capture because the private independent media was fairly successful in staying profitable, producing quality journalism and diversifying its revenue by setting up paywalls.

Just take Dennik N and SME which have some of the highest conversions of paying subscribers relative to population in the world. That tells you it has been possible to build a successful media business in the country.

But as I have written in the piece you mentioned, we see the pressure that has been building up since last year’s election take its toll and first “victims”. Media insiders familiar with the story of media capture in Hungary see the similarities. First, it’s the crack down on public media broadcaster and attempts to bring it under direct state control. Second, it’s the transfer of private media ownership in the hand of oligarchs sympathetic with the ruling regime for various reason. Next, some are warning the next steps will lead to pushing laws identifying some organizations and media companies as “foreign agents”.

Thank you for reading Notes from New Europe. This post is public so feel free to share it.

GG: We know that the spread of disinformation and Kremlin interference, like many countries in the region, has been significant, especially with the Russian war on Ukraine. Do you see connections here?

Dávid: It started during the pandemic, took a few years, and with steady messaging on the far right side started slowly lurking into the mainstream. Also, the steps of the previous government haven’t helped, like when the Prime Minister Igor Matovic in 2021 purchased the Sputnik V Covid-19 vaccine even though it was proven to have been the least effective at the time.

The last elections have showed us that fringe media channels can produce results. Just look at the current Minister of culture. She used to be a famous anchor of the most popular evening news in the country, but was fired because of her controversial posts on social media against refugees. After that she went into politics, drifted from a very conservative party to one more extremist. She also started a show on YouTube that was full of misinformation and hateful speech against minorities. It was enough to get elected to the parliament and become a minister.

GG: I’ve been trying to generate conversations with editors in global media about the importance of covering the full Kremlin war strategy by reporting on state and cognitive capture and not simply marking ground won or lost in the armed conflict. The elections appeared to reveal Slovaks pulling back support for Ukraine, after being the first nation to come to aid them two years ago. Is that part of what you see?

Dávid: Sadly, yes. In a society that is still, after 30 years of independence, looking for its values and ideas, people are more than less susceptible to populist messaging. I read somewhere that having a better education in general, media literacy in particular, serves as a defense against authoritarianism. The problem is that to build such a system you need decades. Even if we started now, the first results would take shape in 10 years. And it’s unlikely a populist government with a strong pro-Russian stance is going to double down on media literacy. If anything, we might expect quite the opposite.

GG: Dávid, thanks for all of this. While it may seem strange given all we’ve discussed, you have always been an important voice for hope and possibility. Can you tell us what gives you hope in what seems like an impossible moment for journalism in Slovakia?

Dávid: I still believe that against all odds we have the advantage of talking about these things before it’s too late, which was the case in Hungary. Slovak journalists are pretty sensitive when it comes to these things. Also, independent media has had years to learn to build sustainable audiences with reader revenue. I think 2024 will be a turning point that will foreshadow where we go in the future. From the way it’s looking now, by any circumstance we will have strong independent media, because we have been building it for years so it can withstand a societal earthquake. The question remains how much pressure will there be on these outlets and journalists working there.

I want to underscore some of Dávid’s point with two relevant examples of what CSD scholars say are among the most important sharp power tools in the Kremlin Playbook: “Supporting both mainstream and fringe political parties often having effective channels of influence over the whole political spectrum,” and “Aligning official Russian government narratives with disinformation and propaganda channels through media capture and other forms of influence.” We need to track both of these tools better in Slovakia and elsewhere.

AND I want to emphasize why keeping an eye on declining freedom for journalism across the region is so critical and should be included more in coverage of the war in Ukraine. Let’s all look for examples of news organization going beyond simply framing relative wins and losses of territory in the armed conflict and helping us understand movement in the information and cognitive front.