Explaining the exasperation with Westsplaining

I was speaking to a colleague about a recent event they participated in here in Sofia. This is someone whose expertise, like that of many of the analysts I am learning from and with, is very impressive. As impressive—if not more impressive—than most experts I booked on radio programs in my heyday back in the States. At this conference, they quietly listened attentively as people from Old Europe held court, and presented an incomplete narrative. The speaker would have benefitted more by switching places and learning from the audience. Classic westsplaining.

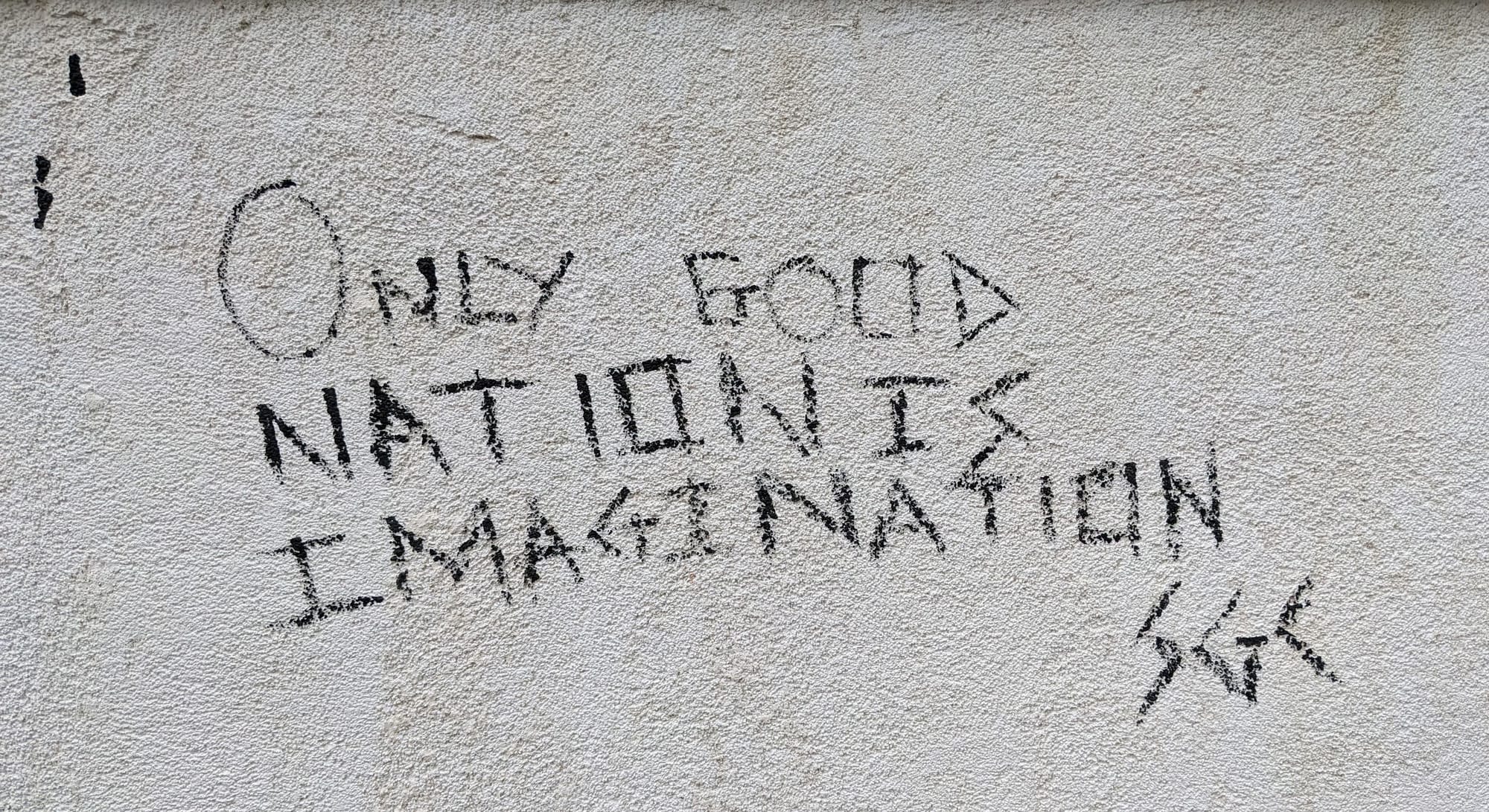

I’ve been witnessing this myself during trips east of Germany for several years, without realizing there is a name for it. I fear I have been guilty of such behavior in the past, and so last summer before coming to the region for this extended stay, I spent some time trying to find techniques that could help me avoid slipping into such a tone. While I’ve largely avoided westsplaining (I hope), I am a witness to it. I see blatant acts of it regularly, and I understand many in the region have come to simply expect it in meetings and conferences with people like me.

People here seem so used to the behavior that when I ask them about it, they shrug it off as something that is just part of the job. In some cases I’ve been told that in order for people to take me seriously as an American “expert,” I need to adopt the practice myself (respectfully, no thank you). To be honest—though not to offer excuses—the structure of most conferences seems to encourage, or at least enable, various forms of ‘splaining. The costs, however, are significant.

Which brings us to a recent article in The Conversation from Viktoriia Lapa of Bocconi University in Milan. Lapa takes us back to 2008, when leaders from the Baltics were warning, during the Russo-Georgian war, about potential Russian aggression elsewhere:

Vytautas Landsbergis, who was formerly the first president of the country’s parliament after independence from the USSR, predicted this war as long ago as 2008. Interviewed by a European news website about the “situation in Georgia”, he bluntly responded: “It is not the situation in Georgia only; it is a very bad situation in Europe, and for Europe’s future, and very promising badly … Who is next after Georgia? … The next is Ukraine.”

This reflects the common theme of experts from the Baltics to the Balkans feeling talked at frequently, and listened to rarely. Kremlin watchers throughout the region understood the threat of Russian hybrid warfare tactics to Ukrainians and Ukraine’s sovereignty before the annexation of Crimea a decade ago, and we see what that led to.

Now to weify a little. I see how powerful—and essential—the collaboration between people from the West and the Balkans and Baltics. We journalists from outside the region—Germany, the UK, and the US in particular—need to reflect on how we framed Kremlin threats and actions following Maidan ten years ago, and with the large scale war on Ukraine two years ago. To what extent did our editorial meetings and planning consider the work of people not just studying regional politics but also living in the region? If we do an audit of the guests we booked, what will it reveal about the lens through which we had listeners vicariously view the war, its causes, and the efforts to solve the crises in the region?

This New Republic piece by Jan Smolenski and Jan Dutkiewicz from March 4 2022 (still early days in the war) called out some significant offenders. They reveal what happens when we don’t listen to the people we are talking about, or even recognize their agency:

Paradoxically, the problem with American exceptionalism is that even those who challenge its foundational tenets and heap scorn on American militarism often end up recreating American exceptionalism by centering the United States in their analyses of international relations. It is, in Gregory Afinogenov’s words, a “form of provincialism that sees only the United States and its allies as primary actors.” Speaking about Eastern Europe and Eastern Europeans without listening to local voices or trying to understand the region’s complexity is a colonial projection. Here the issue of NATO is particularly telling.

Thank you for reading Notes from New Europe. This post is public so feel free to share it.

To be clear, those of us from Western democracies have a lot to share with the people in this region. People who are working hard to protect the best parts of Europe and the EU’s efforts to preserve civic society. Though if our own failures to stem the tide of cynicism, and our addiction to reductionist political discourse have taught us anything, it is that we do not have all the enough answers ourselves. Moving forward, we have opportunities to learn through cross-cultural collaboration, and we can contribute lessons from our own lived and learned expertise. As long as we listen.

Dear reader. We would like to hear from you.

¿What have you read in these notes that has given you pause, and made you want to learn more?

¿Do you have a personal story to share with others curious about how we can effectively build bridges of shared inquiry?

¿Pie or cake?

Please get in touch.

Благодаря,

GG